by Michael Cunningham & Dave Walsh

Part I: I See Dead People »

Dr. John Harbison

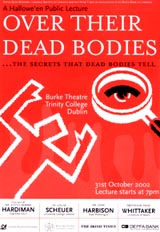

My arrival in the Burke Theatre was typically haphazard and considerably late. I missed Dr. Whittaker’s talk, stumbling in during the appreciative applause, and found some floor to sit on while the bearded Dr. Harbison fumbled with his slides.

Here in Ireland, John Harbison is something of a celebrity. With less than four million inhabitants in the republic, one state pathologist was, for many years, more than enough. Everyone in the country is used to news footage of the tweedy doctor, along with the words ‘…the State Pathologist, Dr. John Harbison, arrived at the scene to carry out a post- mortem examination…’

In recent years, Harbison’s workload has doubled. This may be less to do with any sudden increase in murder than an altered definition of a ‘suspicious’ death. However, Harbison reserved commentary on any change in the murder rate, instead respecting professional demarcation by referring us to the country’s statisticians. While he used to examine some 100 bodies every year, Harbison now looks at around 200, along with Dr. Marie Cassidy, who was appointed Assistant State Pathologist in 1997.

Harbison’s talk was less of a detailed lecture, and more of a cosy wander through his ‘what I did when I certainly was not on my holidays’ slides. At the beginning, he explained that due to size of Ireland’s population, the danger of offending someone with his slides was significant. Some years ago, he was tutoring newly recruited gardai on how best to preserve a crime scene. The slides showed a murder case. a woman who had been killed in a forest. All that was found were some teeth and bones. Afterwards, he was approached by a young garda who asked if Harbison could refrain from using them again. The murder victim was the policeman’s mother.

As if Harbison’s style wasn’t cramped enough, he was unable to discuss any cases of recent vintage – many of which are still in the courts. This didn’t prevent him from discussing several cases in excruciating detail, and with such candid photography that, had anyone connected with the deceased been present, they would have little problem making a positive identification

For me, by far the most disturbing pictures were the burn victims – the ex- US Marine who had torched himself inside a Mini in the Wicklow Mountains, over unrequited love. The woman who had come home from a night on the town, fell asleep, and burned herself to death with a cigarette. We had close-up of a woman, her mouth tinged with blue from the drain cleaner she had swallowed. A man who had been pottering about a scrapyard in Dublin’s docklands, his skull split open by a mad-axe murderer… or rather the bottom of a Guinness keg, which had blown off when he tried to melt it down. I kid you not. And then there was one of the opening pictures… ‘this is a dead man with thermometer in his rectum’.

Another man as pictured on a hotel bed, lying with his back arched, his elbows bent. He had tried to poison both himself and his lover. When Harbison arrived, she was in hospital, and the toxicology report had not been completed – with a cursory glance, the pathologist was able to phone the hospital and tell them what to treat her for – strychnine poisoning (he had figured that it was either this or they had both contracted Tetanus – unlikely).

One of the saddest pictures was the partially decomposed, partially exhumed body of a baby. The details weren’t made terribly clear to us – either the child had died and had been buried by the grieving mother, or the child had died by its mothers hand. Either way, after having been institutionalised for some time, the mother recovered sufficiently to raise a family.

Throughout the talk, Harbison maintained an air of humour, professionalism, and most importantly, compassion. This contributed to a more pure appreciation of the subject matter, and help temper the experience. Still, as each slide was shown, the audience tended to react with either embarrassed laughter or appalled groans. For example, one photograph showed the pale naked body of a man, sitting upright in an armchair, his head bowed. His scrotum looked huge, and red. The initial reaction was to laugh, while wondering why.

Harbison explained that this man had been found in a house just south of the border, but hailed from Belfast. When the gardai saw his body, they assumed that he been subjected to some form of paramilitary torture – so they called in the State Pathologist. It transpired that the man had died from heart failure… and by coincidence, he had a strange condition which involved the swollen scrotum. Mystery solved.

At the question and answer session, while Harbison was shuffling back to his seat, he was asked ‘What is your favourite part of the job?’

Half turning around, and midway through seating himself, he quipped ‘getting home to a warm bed!’

A week and a half after Harbison’s Halloween talk, it was announced that next year a second assistant State Pathologist is to be appointed by the Irish Government. Although the 68-year old Harbison is long due his retirement, he is planning to work on a consultancy basis for a further two years, while clearing his caseload. – Dave Walsh

Dr. Louise Scheur

Dr Scheur’s lecture was an odd one to put on last. Without meaning to detract from her subject matter, it lacked the morbid glamour of the Whittaker or Harbison’s talks, and would have been better as a warm-up act to the blood-and-cuts headliners. In brief – after the Blitz of London in WWII, workers in the shattered remains of St. Giles Church (by Fleet St.) discovered the entrance to the crypt. The crypt had been sealed up many years beforehand, due to fears of cholera outbreaks. It turns out that while lead coffins may preserve our loved ones mortal remains for longer than wooden caskets, it follows that the corpse will decompose at a much slower rate.

Anyway – while archeological researches were being conducted upon the crypt and its occupants, it was discovered that the skeleton of writer Samuel Richardson was contained within one of the coffins. Richardson is regarded as being one of the founders of the modern novel, with his books *Pamela* and *Clarissa* both published in the 1740s. This discovery allowed researchers – in particular Dr. Scheur (it wasn’t clear to me *when* she started studying Mr. Richardson’s bones – presumably she hadn’t been doing it since WWII) to compare the skeleton with the writers papers.

Richardson was something of a hypochondriac, and many letters between himself and his doctor still exist, with the celebrated author complaining of one ailment or another. In addition, descriptions of himself were found, which included his portly bearing, his ruddy features, and his disinclination to turn his head – instead pivoting his entire body.

On examination of his spine, it was discovered that Richardson suffered from ‘diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis’ – in other words, his spine had fused in several places.

Interesting stuff. Not quite as gory and entertaining as Dr. Harbison, or, I gather, Professor Whittaker.

Dave Walsh

Part I: I See Dead People »