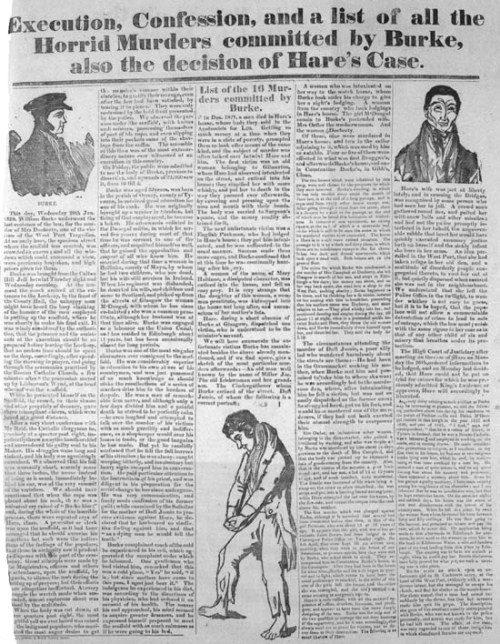

178 years ago today, an Irishman named William Burke was executed in Edinburgh, Scotland. You may never have heard of him, but at the time of his death he was infamous: ‘This day, Wednesday 28th Jan, 1829, William Burke underwent the last sentence of the law, for the murder of Mrs Docherty, one of the victims of the West Port Tragedies. At an early hour, the spacious street where the scaffold was erected, was crowded to excess ; and all the windows which could command a view, were previously bespoken, and high prices given for them.’

So begins the Broadside which was posted on the streets of Edinburgh in 1829, informing those who could read it that William Burke, one half of the infamous Burke and Hare, had been sent to the gallows and hung until dead. A Broadside, in case you were curious, was the popular means of mass communication in the days before affordable newspapers: a large, detailed sheet of paper slathered to a public wall.

‘…betwixt Tuesday night and Wednesday morning…’

This is the full Broadside, as it appeared at the time:

Should you wish to read it, a full transcript of the Broadside is also available.

‘His struggles were long and violent…’

The sequence of events which led Burke to the gallows are now the stuff of legend. Previously, in Waking the Dead, we had covered the emergence of the Resurrection Men (or body-snatchers) and explored the booming industry that was the illegal trade in cadavers to medical schools. What separated Burke and Hare from the other dealers in dead body parts, was the simple fact that they didn’t wait for bodies to be buried: they cut out the middle man (Death) and produced the bodies themselves.

From the BBC:

Acting on a strict code of ‘no questions asked’, the financial rewards of Burke and Hare’s crimes led to a series of 16 murders spanning a period of just under a year. And had the two criminals not allowed their greed to consume them, they may never have been caught…

Murder for money is not an original concept by any means, but Burke and Hare had a new perspective on killing for financial gain. Unusually, they had little interest in the wealth of their victims, all they needed was a fresh corpse to sell.’

‘…one of the most singular characters ever consigned to the scaffold’

Burke and Hare first met in Edinburgh: two immigrants who had left their homes in Ireland to work on the Union Canal in Scotland. When Burke moved from Leith to West Port, with his partner Helen McDougal, he and Hare met by chance.

Hare had taken lodgings at a boarding house with a widowed woman named Margaret. History relates that they had a close relationship, not long after Margaret’s husband’s death, with the two running the house as though they were a married couple.

Margaret then introduced Hare to both Burke and his partner Helen McDougal. Not long after the couple became paying lodgers. It’s unclear exactly how it was the murderous scheme was hatched, but it would seem that it could have been entirely by fortuitous chance: a lodger at the house, an old man named Donald, became ill and died there. Donald owed Hare £4 in rent. And, rather than seek out compensation from a family member, Hare had a better idea: sell the body.

Burke and Hare swapped Donald’s body with a sack of bark on the day of the funeral. Later they took the remains to the offices of Professor Robert Knox. They were paid 7 pounds and 10 shillings for their efforts – a tidy sum for the time.

Although Donald was not murdered, simply sold for parts, he is often counted as one of the victims. This explains why there seems to be some variation in the number of victims between the figures of sixteen and seventeen.

But the next cadaver to land on Knox’s desk (who, by the by, never faced any criminal charges) was that of a murdered man. Again, from the BBC:

Another of Hare’s lodgers, a miller named Joseph, had fallen ill not long after Donald’s death. Though he was not seriously ill, Burke and Hare took it upon themselves to put an end to his suffering.

After several glasses of whiskey with the two men, Joseph passed out. And by holding his nose and mouth closed whilst the other restrained him, Burke and Hare had, by chance, discovered their very own signature murder method. By suffocating the victim, they provided the anatomy students with the fresh, undamaged cadavers that they needed.

And thus it began: an eleven month killing spree, resulting in a trial so shocking that it seems to have resulted in changes to the law.

‘…the most frightful yell…’

When they were finally arrested, the Burkes appear to have come off rather worse than others: after a month of prevarication, the Hares cut a deal with the Police, squarely placing the blame for all criminal activities at the door of the Burkes. Furthermore they then testified against them in the sensational trial of December 1828.

On Christmas morning, William Burke was sentenced to death. Helen was set free: disappearing, eventually, to Australia. Burke was hung at the end of January, on the 28th. There was a large crowd gathered to witness the event:

‘When the body was cut down, at three quarters past eight, the most frightful yell we ever heard was raised by the indignant populace, who manifested the most eager desire to get the monster’s carcase within their clutches, to gratify their revenge, even after the law had been satisfied, by tearing it to pieces. They were only restrained by the bold front presented by the police.

We observed the persons under the scaffold, with knives and scissors, possessing themselves of part of the rope and even slipping into their pockets some of the shavings from the coffin. The scramble at this time was of the most extraordinary nature ever witnessed at an execution in this country.’

Quite what became of Hare is something of a mystery. Some reports indicate he was seen a blind, vagrant beggar, wandering the streets of distant London. Others purport that he was stoned to death there in a limepit. His last sighting seems to have been in Carlisle.

The Anatomy Act 1832

The fallout from the case extended far beyond the gathering of an angry mob. A quote from the Lancet, cited at Wikipedia, summarises the effects of the case:

The murders highlighted the crisis in medical education and led to the subsequent passing of the Anatomy Act 1832, which expanded the legal supply of medical cadavers to eliminate the incentive for such behaviour. About the law, the Lancet editorial stated:

‘Burke and Hare … it is said, are the real authors of the measure, and that which would never have been sanctioned by the deliberate wisdom of parliament, is about to be extorted from its fears … It would have been well if this fear had been manifested and acted upon before sixteen human beings had fallen victims to the supineness of the Government and the Legislature. It required no extraordinary sagacity to foresee, that the worst consequences must inevitably result from the system of traffic between resurrectionists and anatomists, which the executive government has so long suffered to exist. Government is already in a great degree, responsible for the crime which it has fostered by its negligence, and even encouraged by a system of forbearance.’ (Lancet editorial, 1828-9 (1), pp 818-21, 28.3.1829)’

Find out More

The William Burke Broadside (transcript)

‘Word on the Street’ – The National Library of Scotland’s on-line collection of nearly 1,800 broadsides.

BBC Crime Case Closed

Burke and Hare: The Year of the Ghouls

Images

Broadside image from the collection of the National Library of Scotland.

Waking the Dead

Full list of all articles in the Waking the Dead series

Sponsored Link: Dublin Law Jobs with Benson & Associates »