Last week we were some way into showing how Henry Hurt’s Reasonable Doubt shows that Oswald did not commit murder beyond a reasonable doubt. Let doubt be our guide as we proceed…

Last week we were some way into showing how Henry Hurt’s Reasonable Doubt shows that Oswald did not commit murder beyond a reasonable doubt. Let doubt be our guide as we proceed…

Oswald and the rifle

Hurt’s first quibble with Oswald’s rifle shooting is that in investigative re-creations of the scenario, marksmen for both the Warren Commission (WC) and the HSCA could not fire three shots from the 6th floor of the Texas School Book Depository within the time frame and hit the targets. Was Oswald better than any of these shooters, then? (p.101).

There also had to be an ammunition clip for the gun to be fired that fast, i.e. otherwise ‘the cartridges must be hand-loaded, one by one’ (p.103), but Hurt points out there is no mention in testimony of an ammo clip being found.

The ammo itself tells a strange story, but I’m confused about Hurt’s logic. He wrote, as we covered last week, that the Western Cartridge Co. made batches of the ammo in 1954 but also a lot of it in WWII that was sent to Italy and then sold back to the US market after the war. So on p.86 Hurt wonders ‘If in fact the cartridges believed to have belonged to Oswald came from this, earlier, batch of Western ammunition…’ but on p.106 ‘It seems clear’ to him that the ammo was the earlier, WWII batch. How did he reach that conclusion?

During the HSCA investigation, an FBI memo was found from December ’63 which showed that Western Cartridge made some of this ammo for the Marine Corps in 1954. Hurt does not say if this Marine batch is one of the 1954 batches that Dr. Guinn based his tests on, or all of those batches, or an extra one. I suppose if all the ’54 ammo was for the Marine Corps, it would explain why Hurt assumes the rifle had the WWII ammo. But here’s another thing. The FBI memo states the ammo ‘does not fit and cannot be fired in any of the [Marine Corps] weapons. This gives rise to the obvious speculation that it is a contract for ammunition placed by the CIA with Western under a [Marine Corps] cover for concealment purposes’ (p.106). This would mean the CIA was using the very same sort of rifle that that Lee Harvey Oswald apparently bought before the assassination!

There is doubt that the rifle that was Oswald’s, and featured in all the evidence so far, was really the rifle found on the 6th floor that day. Testifying to the WC, three of those who found and saw the rifle ‘before it was removed’ remember it as a Mauser. One of them, Deputy Sheriff Roger D. Craig, even remembers Mauser ‘stamped on the barrel’ (p.102). It was reported as a Mauser for about 12 hours. This may be a case of the first reported information not being the correct information, but it’s a little strange all the same.

Finally, it should be noted that there is a dispute over the palm print found on the rifle. Dallas police did not announce they had a palm impression taken from the rifle until the night of 24 November. They had the rifle on the 22nd, then it was taken that night by the FBI, who could not find any print of Oswald’s on it in their lab, and they returned it to the Dallas police on the 24th. It seems that during the 24th, prints were taken from Oswald’s corpse in the morgue. The police announced the palm print find that night, and it was returned to the FBI who found it there too on the 26th. Vincent Drain, the FBI agent who collected the rifle from the Dallas police the first time (on the night of the 22nd), believes the Dallas police added the print on the 24th, the print being, in his words, ‘some sort of cushion, because they were getting a lot of heat’ (p.109).

James Tague

Dealey Plaza witness James Tague (b.1936, still living) was standing near the Triple Underpass and during the shooting ‘felt a sting on his cheek’ (p.131). A policeman saw that Tague was bleeding from his cheek and it seemed that Tague had been hit by a ricochet off the curb. News photographers took images of the curb and the story was widely reported in the media.

But the FBI and the WC downplayed and ignored Tague and the curb in their investigation. It seems that initially they thought all 3 shots hit the limo. And something very strange happened in May ’64: Tague returned to the scene to take his own photograph of the curb, and the bullet damage was gone! Then there seems to have been a sea change among the authorities in June, as the single bullet theory (SBT) began to take hold in the WC (the WC version of events involved a shot that missed, but was inconclusive over which one of the three it was; the HSCA concluded that the first shot missed, and that it was fired at frame 160 of the Zapruder film) and the SBT’s author, Arlen Specter, wanted to know ‘where the missing bullet struck’ (p.134). Feeding into interest in the curb now was the fact that glossy photos of the damage existed. No-one could explain why the curb was now smooth. Perhaps it had been smoothed over by cover-up men during a time period when they thought all three bullets hit the limo, and any other bullet damage was evidence of another shooter? Or perhaps it was always evidence of another gun? The curb was altered, that is all that is known.

The Tippit crime scene

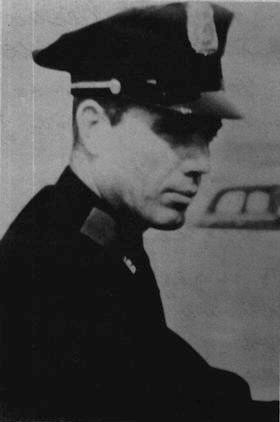

The basic story of the Officer Tippit murder was that he was in the Oak Cliff area, a populated suburb with people around, and talked to someone on the street from his patrol car. Then he got out of the car, and was walking round it, towards the person, when this person opened fire and shot the police officer dead. This took place 45 minutes after the JFK assassination. Oswald was seen acting suspiciously in the area, ducking into a cinema without paying. Police arrested him there. During the arrest he apparently drew a gun on them, and this revolver was later linked to the Tippit shooting. When the police learned he worked at the Book Depository, it seemed he was the President’s assassin too. But like the crime in Dealey Plaza, in many ways the evidence from the Tippit crime scene doesn’t fit Oswald, and a defence attorney could have made much of the following.

1. For technical reasons, no bullets could ever be linked to the revolver because it couldn’t mark them. This meant it was only the shells left on the ground after the shooting, and not the bullets in Tippit’s body, that were linked to the revolver. There was no way of telling when these shells had been fired, which leaves the possibility open of framing Oswald by leaving old shells of his at the scene (pp.143, 152). As was mentioned on this blog before, there’s also the problem of the shells not matching the bullets, unless five shots were fired and there is one missing bullet and one missing shell.

2. It seems that if Oswald was the killer, there was not much time for him to get the scene. He was seen at the Book Depository just after the Kennedy assassination. Then his landlady, Earlene Roberts (Oswald stayed in Dallas during the week because he worked there; Marina and their children lived in another town, Irving, and he joined them on weekends), met him when he came home for some minutes, at one o’clock. Domingo Benavides, one of the witnesses to the Tippit murder a mile away, contacted the police after ‘a few minutes’, and a report was ‘officially logged at 1.16pm’ (p.144), so Tippit was dead by then. This timing agrees with the presence of witness Helen Markham, who was on her way to catch the 1.15 bus when she saw the murder. Could Oswald have walked a mile in about 10 minutes? Oswald was not seen on the route, and certainly not conspicuously running.

3. The eyewitnesses didn’t really identify Oswald. Markham’s testimony was confused and bizarre (she picked out Oswald in a lineup because of a ‘weak feeling’) (p.146) and the best-placed witness, Benavides, couldn’t identify him (at the time – but he apparently could on TV in 1966!) (p.145). Warren Reynolds, who saw a man running from the scene, wasn’t interviewed by the FBI until 21 January, and then he ‘could not definitely identify’ Oswald (p.148). Two days later, someone shot him in the head. He survived, and appeared before the WC in July, identifying Oswald like a man who could take a hint. Other Tippit witnesses included Frank and Mary Wright, who lived on the street (East Tenth St., incidentally). When the shots rang out, Mary phoned for an ambulance and Frank ran outside. Far from seeing Oswald depart the scene on foot, Frank saw a man in a long coat get into a grey coupe and drive off (p.149).

4. Witnesses reported that ‘the gunman was walking west toward Tippit’s car prior to the shooting’ (p.149). If Oswald was coming from the Roberts rooming house, he had to be walking east. Otherwise you have to add double-backing to his 10-minute sojourn through Oak Cliff.

5. Why did Tippit stop his car to talk to his killer? He had a clipboard in his car for taking notes, so he may have noted the conversation with the killer, prior to the shooting (p.150). But apparently no-one ever read the clipboard.

6. The man seen running from the scene (by Reynolds? Hurt doesn’t specify which witness) abandoned a jacket, which, investigators discovered, had never been on sale in Texas or Louisiana (States where Oswald lived). Similarly, a dry cleaning tag on it could not be traced to any location associated with Oswald (p.151).

7. Putting a mark on the shells found at the scene was a ‘routine matter in the proper handling of evidence’ (p.153). Officer J. M. Poe marked them with his initials. Later, when asked to identify the marks for the FBI, he couldn’t. Henry Hurt himself looked at the shells in the National Archives, and the Poe markings aren’t there (pp.153-4).

8. The ‘revolver supposedly taken from Oswald’ was not marked as evidence at the time it was seized (p.157).

9. Tippit was found outside his usual patrol district. He was 3 miles from the centre of the area he was supposed to be patrolling. Transcripts of relevant police radio transmissions revealed no reason for him to be there. Then, another transcript was sent to the WC in spring ’64, which included an instruction at 12.45 telling Tippit to ‘move into central Oak Cliff’. But why would he be sent there in the midst of the emergency surrounding the President’s murder? Hurt speculate that this order may have been dubbed onto the radio by Tippit’s cop buddies, after the fact. Tippit does not even acknowledge the order in the transcript (pp.159-61).

And now it’s time to move on from Reasonable Doubt. It covers much of the same ground as The Kennedy Conspiracy, although each book very often has different details, which makes them superb companions. Hurt’s book also explores tangents Summers doesn’t bother with – like the Garrison investigation, and the Robert Easterling ‘confession’ – but Summers’ book is a decade more up-to-date (e.g. Hurt would have been happy to see the photo in Summers’ book of Oswald and David Ferrie together).*

*Blather update: a reference here to French terrorist Jean Souetre has been deleted. Upon reflection, The Kennedy Conspiracy seems no more up-to-date on that matter than Reasonable Doubt. Compare Summers p.462 to Hurt p.416.

- Who Shot JFK?

- The Kennedy Conspiracy

- Reasonable Doubt (part one)

- Reasonable Doubt (part two)

- Who’s Who in the JFK Assassination

- Deep Politics and the Death of JFK

- Deep Politics II: Oswald, Mexico, and Cuba (part one)

- Deep Politics II: Oswald, Mexico, and Cuba (part two)

- Oswald and the CIA (part one)

- Oswald and the CIA (part two)

- Marina and Ruth

- Oswald and the CIA (part three)

- Wilderness of Mirrors

- Perils of Dominance

- JFK and the Unspeakable

- Z-∞