Continuing directly from the last entry, we examine more of John Newman’s trawl through the declassified files in his book Oswald and the CIA (2008 edition). Government interest in Lee Harvey Oswald began with his defection in October 1959 and continued until ’63. It’s time to look now at his controversial ‘redefection’ from the USSR back to the USA in June ’62.

Oswald’s ‘redefection’

It has often seemed curious to the conspiracy theorists, and indeed many others, that Oswald, who defected to the USSR, was allowed to defect back to the US without being punished by the American authorities, causing some people to think he was a secret agent. But we dealt with the issue of Oswald being a ‘dangle’ in the last entry and it is highly unlikely he was a spook.

One of the main factors that it was so easy for Oswald to come back is that he never renounced his American citizenship. He called into the American embassy in ’59 only once, left his passport, and never filled in any forms. So when he expressed the desire to return, that was one obstacle that was not in his way. However, if he ‘wanted to come back to America’, the embassy let him know ‘he would have to take his chances’ (p.207) about being prosecuted for espionage for going over to the Soviet Union, where he lived as a factory worker in Minsk. The process of ‘redefecting’ took a long time: he first expressed interest in returning in December ’60 and it took a year and a half. In the meantime, JFK was inaugurated (20 January ’61), the CIA’s Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba failed (16-17 April), and Anatoli Golitsin defected to the US (December).

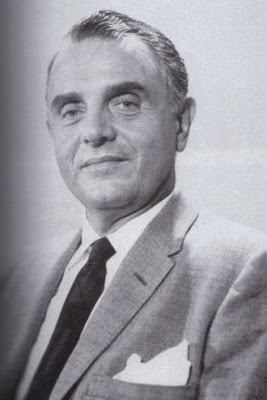

Richard Snyder

When Oswald visited the American Consul Richard Snyder in Moscow in July ’61 ‘he groveled before Snyder with uncharacteristic humility, pleading that he had “learned a hard lesson a hard way”‘ i.e. that the Soviet Union was no utopia (pp.224-5). Snyder’s judgement was that Oswald had ‘matured’ and he let him sign an application for a new passport (which was due to expire in September) and let Marina sign a visa application (p.225). Lee had married her on 30 April, and on 25 February ’62 their daughter June was born and she too became included in the exit plan.

Oswald had a lot to thank Snyder for. It was the embassy that told the State Department in Washington ‘that Oswald had not committed any expatriating acts, and that his American passport should be returned so that he could begin the application process for a Soviet exit visa’ (p.225). The FBI field office in Dallas also went with the Snyder interpretation. They later reported that Oswald’s anti-American statements made at the time of his defection were ‘necessary to make this propaganda because at the time he had wanted to live in Russia’ (p.235).

The U-2

Upon Oswald’s return to US soil, the FBI interviewed him and, in the words of Dallas special agent John W. Fain, the redefector ‘denied that he went to Russia because of his lack of sympathy for the institutions of the United States or because of an admiration for the Russian system’ (p.265). And while there is no proof that Oswald gave U-2 information to the Soviets, he had voiced intentions on helping the Russians at the time of his defection, and the only proof he didn’t provide information was in his flat denial to the FBI upon his return (p.267). He now worked in a sheet metal factory which was not a sensitive job for an ex-defector to be doing. The FBI left it at that and closed his file (p.270). However, he soon began subscribing to communist literature and writing to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in New York (p.274).

George de Mohrenschildt

Oswald in Texas, June ’62-April ’63

When the Oswalds moved to Texas, they fell in with a Russian-speaking milieu, especially with the avuncular emigré gent George de Mohrenschildt, a petrolium geologist, who said he checked with his FBI and CIA contacts and decided young Oswald was ‘OK’ to associate with (p.276). This ties in with the Dallas FBI’s conclusions about Oswald. The CIA agent that de Mohrenschildt checked with was J. Walton Moore, the Dallas CIA Domestic Contacts Service chief. This connection has made people wonder if de Mohrenschildt was ‘a CIA “control” for Oswald, with Moore as the reporting channel’ (p.277). Newman thinks this is unlikely, as CIA Domestic Contacts dealt with ‘routine contacts and debriefings’ (p.277). But de Mohrenschildt was also friends with another CIA man, Nicholas M. Anikeeff, who in ‘a recent interview… refused to disclose what part of the Agency he had worked for’ (p.278), but Newman concludes from other sources that Anikeeff worked for the Soviet Russia Division.

Newman doesn’t have anything else on de Mohrenschildt in the files, but it’s always been interesting that on ‘the day he agreed to an interview with the HSCA, he was found dead of a gunshot through his mouth’ (Benson, Who’s Who in the JFK Assassination, p.111).

This inspection of Oswald and the CIA will go to a third part, but we are coming to a very important anniversary on Friday, so the next blog entry will be published on that day and will focus on something pertinent to that, in Texas in October ’63, before we go back to the rest of Newman’s findings, which cover Oswald in New Orleans, April-September ’63; the Odio Incident, September ’63; and Oswald in Mexico, September-October ’63. It’s only then I’ll fill you in on Newman’s surprising ‘Epilogue, 2008’.

- Who Shot JFK?

- The Kennedy Conspiracy

- Reasonable Doubt (part one)

- Reasonable Doubt (part two)

- Who’s Who in the JFK Assassination

- Deep Politics and the Death of JFK

- Deep Politics II: Oswald, Mexico, and Cuba (part one)

- Deep Politics II: Oswald, Mexico, and Cuba (part two)

- Oswald and the CIA (part one)

- Oswald and the CIA (part two)

- Marina and Ruth

- Oswald and the CIA (part three)

- Wilderness of Mirrors

- Perils of Dominance

- JFK and the Unspeakable

- Z-∞